Source:ABC

Spanish newspaper ABC recounter a diplomatic effort “in extremis” to stop the war between the United States and Spain

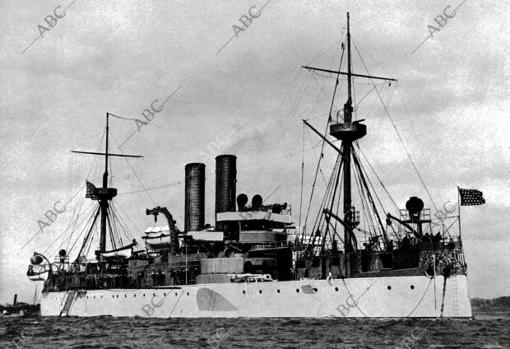

The United States battleship ‘Maine’, destroyed in the bay of Havana in February 1898, with loss of many lives, was blown up by an internal explosion, and when the- ship is lifted from the bottom of the bay it will be seen that the Spaniards in Cuba had absolutely nothing to do with the destruction of the ship. This is the opinion of the officers of the War Department, based on the reports supplied to them by Army officers, who are engaged in the removal of the moldy helmet.

People who have recently arrived from Washington and who have full knowledge of the work on the lifting of the battleship are known to agree that the destruction of the ‘Maine’ was due to the explosion of one of the hermetically sealed compartments used to store ammunition. This theory is born from the facts already developed. A large amount of coal has been found in the mud surrounding the hull of the ‘Maine’. Human bones have also been found outside the helmet. This, it is believed, is proof that no outside force could be used to blow up the ship“.

El buque de guerra «Maine» en una fotografía de 1896

ABC collected in January 1911 the results of official investigations of the ‘Maine’ disaster, as published in The New York Times. Then something that many defended in 1898 was confirmed: that Spain was not involved in the blowing up of the battleship that precipitated the declaration of war by the United States.

On February 26 of that fateful 1898, “Blanco y Negro” had reported the explosion of the ‘Maine’ pointing out that the event had been ‘obviously accidental’. Expert reports were given by the divers after recognizing the wreckage of the ship which “reinforce the version that all Spaniards gave from the first moment: only a casual and internal accident could produce such a horrible catastrophe on a ship so well defended from outside agents as the North American battleship was”, the magazine explained. The possibility that the US government had caused the explosion to have an excuse to go to war with Spain was not even considered by the magazine. Perhaps because of the 355 crew, 254 sailors, and two American officers died.

It recognized, however, that the event “could not occur in a worse time”. “Our relations with the United States were strained as ever, not only as a result of the Dupuy de Lome incident, but also because of the very presence of the North American ship in Havana; it was certain that the jingoist press would make the most of it; the arrival in New York of our cruise ship ‘Vizcaya’ was near, which could be the object of any dangerous manifestation on the part of the exalted North American populace, and, finally, the Carnival festivals themselves could give margin in Madrid or in the provinces to any incident that, beginning as a carnival joke, it ends in serious international conflict”.

Madrid, February 1898. The United States consulate in Madrid, guarded by the Civil Guard, after the Maine explosion in Havana. – Irigoyen

Ten days before the explosion of the ‘Maine’, none of this had happened, and “Blanco y Negro” believed, wrongly, that the dense clouds had been left behind. “The Yankee government has not been carried away by the “jingos”, it said without knowing that it would report on the war shortly after.

A failed fix

As published in 1910, there was a diplomatic attempt “in extremis” to avoid conflict. At least, that’s how a close friend of the then English ambassador to Washington, Sir William Pauncefote, explained to the New York Herald. Briton Moreton Frewner stated that in 1905 he attended a dinner at the home of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, where he met with politician and diplomat Wayne McVeagh and George B. McClellan, mayor of New York. The conversation turned to the Spanish-American war and McVeagh referred to the following:

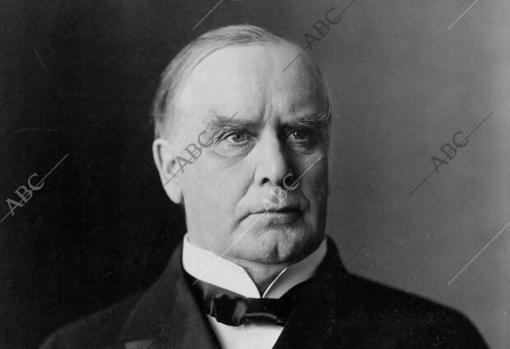

William McKinley, President of the United States

The Friday before the declaration of war, I was at the White House to visit President McKinkey, whom I found gravely concerned. “The public excitement – he told me – will inevitably lead us to war. We are not prepared. Spain must be prepared for a long time for such a contingency. We find ourselves in a more serious conflict than can be supposed. I do not know which side to take”.

Upon learning of McKinley’s plight, I replied by offering an acceptable solution. “Do what you like”, the president replied in a tone that revealed a certain distrust of the result.

Right after that, I wrote a telegram addressed to the Government of Madrid, and in which I made three claims, namely:

- That from now on, the relations between Spain and Cuba should be similar to those between England and Canada.

- That an international tribunal be appointed to determine the matter of the ‘Maine’ blasting.

- That a six-month armistice be granted to the [Cuban] insurgents.

McKinley read it and signed it, saying at the same time: “I have no hope of settlement. Spain is a proud people and in no way will it want to agree. We will go to war, without remedy.”

The next day, at night, we received the reply from the Spanish Ministry. Spain consented to what was proposed, with minor modifications aimed at giving a decent form to the agreement.

These words of McVeagh were completed by Senator Lodge.

Senator Davis, Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and I went to the White House on Monday morning. We saw the telegram and the response given by the Spanish Government. I expressed the opinion that the Congress would not be satisfied with that arrangement. Spain had to renounce all sovereignty in American territory, since the pages of its history regarding the New World were full of horrors and excesses. The Yankee people were urgently waiting for a strong verdict against that country.

Hearing my words the President cut me off with a gesture. “I was expecting your objection, Senator”, McKinkey said, pressing a bell button. As soon as it rang, a secretary appeared bringing a sheet. “You will see what I am going to transmit right now”, added the president, showing us the document. It was the categorical demand that Spain evacuate the Antilles without delay of any kind.

Senator Davis and I headed for the Capitol. In secret session, we notified our colleagues that an ultimatum had just been cabled to the Spanish Government.

Tuesday passed without a reply. Wednesday passed, and the Madrid Cabinet persisted in its silence. Then, supposing that Spain delayed its reply to make its war preparations in the meantime, we hastened to break out hostilities.

A long time later we learned with surprise that the famous ultimatum never left McKinley’s hands.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021