Source:Sonrisas en el camino

Bartolomé de Medina, the metallurgist

Today I am not going to talk about conquistadores or sailors, about men and women who made history. I will dedicate these lines to neither battles nor transcendental events, treaties or discoveries. Today I will write about metallurgy, cinnabar, mercury and precious metals. And what does this have to do with the History of Spain? Quite more than you might think, for what would have become of American silver without the mercury of Almadén? What would have happened if Bartolomé de Medina had not discovered a way to separate silver from the rest of the metals? It would have been a different story. And it is in the details where the difference lies.

Bartolomé de Medina was born in Seville in 1497 and became a prosperous merchant. He had contact with a German metallurgist (he called him “master Lorenzo”) who passed on to him the secrets of how to process silver and gold in a very economical and different way to that which had been used up to that time. And after several experiments in Spain, they decided to go to New Spain. The crown did not give permission to the German metallurgist, so only Bartolomé travelled.

Once in New Spain, in 1554, his experiments were of great importance and of great interest to the king. And after much experimentation, he discovered the process of amalgamation of silver, which is produced thanks to the affinity that this element has with mercury. And he did it in the mines of Pachuca and Real del Monte. This process is called “Beneficio de Patio” and was very important for Mexican mining and, in general, for the whole of Hispanic America.

Beneficio de Patio, the process

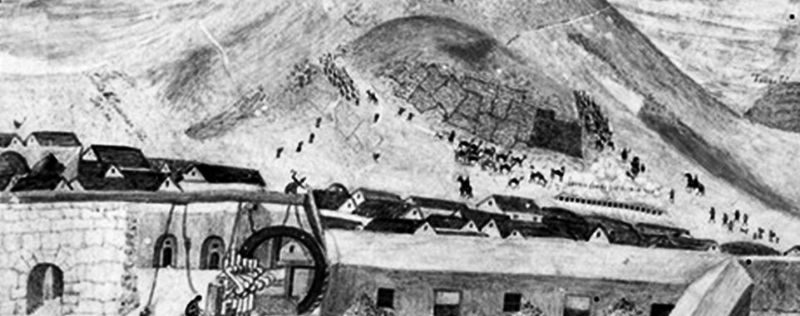

But it was not an easy process, it was very difficult to find the right path. Medina settled in Pachuca, because of its growing mining fame and its proximity to Mexico City. There he began to build the hacienda of the Purísima Concepción, on the slopes of the Magdalena Hill, next to the Avenidas river. There he put into practice everything that his beloved master Lorenzo, the German metallurgist, had taught him:

Grind the ore very fine, stir in charged brine, add quicksilver and mix well. Repeat the stirring daily for several weeks. Each day take a sample of the slurried ore and examine the quicksilver. See. It is bright and shiny. Over time it should darken as the silver minerals are broken down by the salt and the silver forms an alloy with the quicksilver. The amalgam is pasty. Wash the depleted ore in water. Burn the surplus amalgam; the mercury is gone and the silver remains.

It wasn’t all plain sailing, it wasn’t all so easy and pretty. In spite of following the instructions to the letter, in spite of trying and trying again and again, in spite of the efforts made, the method did not work, the expected reaction did not take place. Until he discovered that, in that mixture of salts and mercury, a catalytic agent was missing, the masterly iron sulphate (copper). Therein lay the key to the process.

And why was it called patio “beneficio de patio”? Well, the mixture of pulverised ore with water, salt, mercury and other compounds was spread out to form “cakes” in very large courtyards (patios in Spanish). There, the reagents were added and mixed, taking care that the reactions took place properly so that the silver would amalgamate with the mercury. After several weeks, the cake, once it had been washed to remove the materials that had not been left behind, was placed in a furnace so that, with great care, the mercury could be volatilised, leaving only the silver in a spongy form. This silver was finally melted down to obtain white metal bars.

Almadén and mercury

Thanks to Bartolomé it was possible to separate the silver (and the gold) from the rest of the metals, as the silver was extracted, let us say virgin, from the mine and had to be amalgamated. This process helped to extract the pure silver so that it could be sent in galleons directly to Spain. But for this, huge quantities of mercury were needed. And for this, we have to go to the town of Almadén (Ciudad Real).

It is known that quicksilver was already being extracted 2000 years ago, but these Almadén mines became extremely important when the discovery of large deposits of gold and silver in the New World became known. The Catholic Monarchs already had an intuition of the importance of mercury for obtaining wealth, when in 1512 they turned its extraction into a royal monopoly, which brought great benefits to the crown. But that monopoly was lost when Carlos I, his grandson, ceded those rights to German bankers (the Fuggers) in exchange for funds to buy the imperial throne.

Cinnabar was extracted from the Almadén mines, from which mercury was obtained (it is believed that one-third of the mercury consumed by mankind since time immemorial has come from Almadén). The same, in enormous quantities, loaded onto ox carts, was taken along inhospitable roads, along ravines and paths, crossing the Sierra Morena, on a long and dangerous journey, until it reached the port of Seville. There it was shipped to the New World so that, together with the salts and reagents, it could amalgamate the silver, separate the silver from the minerals. A whole set, a whole process to change the history of mining.

After a period of crisis, when there was a shortage of labour, the Fuggers pushed for the use of prisoners in the mines. Hence, a prison was built in Almadén, directly linked to the mining complex. Quicksilver would not be lacking in the New World to extract the valuable mineral. The Royal Prison for forced labourers in Almadén was built in 1754. But also, in 1785, Almadén hosted the first mining school that existed in Spain.

Details that make an empire, alchemy and knowledge that amalgamate reasons and advances towards the future. And it all adds up, every detail counts. Bartolomé de Medina, the metallurgist who changed the way silver was extracted and Almadén, the town that made an important place in the history of Spain.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021