Source:Medigrafic

This article outlines the most outstanding figures of indigenous, European and Creole physicians and surgeons who practised their art in New Spain during the 16th century.

There were surgeons, rather improvised, in the Spanish armies that confronted the inhabitants of these American lands in the name of the empire and the universal church. But there were also natives, who perpetuated ancestral traditions by organising themselves around a focus of great culture: the Franciscan College of the Holy Cross in Tlatelolco. At the dawn of the New Spain, doctors and surgeons trained in centres of high medical level such as Seville, Salamanca and Alcalá de Henares arrived. In addition, a remarkable exchange of medicinal plants and, in general, of therapeutic products between the Old and the New World began. Medical books printed in Europe soon began to be introduced here and, in the second half of the century, the first Novo-Hispanic medical books appeared. Once the initial chair of medicine at the Royal University of Mexico was established, the number of medical publications increased until, in 1598, the first medical thesis printed in America was published.

During the Conquest

Spanish Surgeons

Some improvised surgeons arrived on Mexican shores with Cortés’ expedition. In fact, in the chronicle of Bernal Díaz del Castillo,1 it is mentioned that after the first battles against the Tabasco Indians, “the soldiers’ wounds were dressed with cloths, for there was nothing else, and the horses were cured by burning their wounds with the ointment (melted tallow) of one of the dead Indians, which we opened to remove it…”.2 Also “with the ointment of the Indians… our soldiers were cured, there were fifteen of them… and even four horses that were wounded…”.3 The list of Cortés’ companions mentions a “soldier who was called the bachelor Escobar; he was an apothecary and a surgeon…”. Juan del Rey, who followed the conquistador Francisco de Montejo throughout the Yucatán campaign, is also mentioned as “herbalist, physician and surgeon”.4

Regarding the episode of Pánfilo de Narváez, who arrived from the island of Cuba on the beaches of Veracruz, Bernal Díaz says that “he was very badly wounded and his eye was broken, and he asked Gonzalo de Sandoval for permission for a surgeon he had in his navy, who was called Maestre Juan, to cure his eye and that of other captains who were wounded…”.5 On the other hand, there was “a black man full of smallpox… who caused the whole land to swell and swell with them…”.6

During the siege of Tenochtitlán, the Spaniards had no lint or bandages and, for the wounded, they used indigenous cotton fabrics, torn from the corpses: “we cured our wounds by burning them with oil, and a soldier who called himself Juan Catalán sanctified and salved them…”.7 It should be borne in mind that, at that time, it was also customary in Europe to pour very hot elderberry oil on wounds. This lasted until Ambroise Paré (1509-1590), military surgeon in the army of Francis I of France, during the Piedmont campaign (1536) began to apply the so-called gentle treatment to gunshot wounds. In turn, the Bolognese Bartolomeo Maggi (1516-1552) experimentally demonstrated the non-toxicity of gunpowder on such wounds and began to treat them with soothing medicines, rest and diet.8

After the capture of the great Tenochtitlán, the conquistadors found themselves in straits because of the high prices of whatever they had to buy and whatever services they needed. Thus, mention is made of a surgeon, Maestre Juan – probably the one who arrived with Narváez – who cured some bad wounds and was matched by the cure at excessive prices, and likewise “a sawbones, who was called Murcia and was an apothecary and barber, who also cured…”.9

Proto-nurses

The most popular of the women who acted as nurses was probably Isabel Rodríguez,10 one of the few women who arrived with Cortés. During acts of arms, she healed and comforted the wounded and, on occasion, entered combat or stood guard if soldiers were in short supply or fatigued. With her was María de Estrada, wife of Alonso Martín, who is mentioned in Francisco Cervantes de Salazar’s Crónica de la Nueva España.11 Bernal Díaz defines them as “old women” when he mentions their presence at the banquet offered by Cortés in Coyoacán after the fall of the Mexican capital.12

Mention is also made of Beatriz González and Beatriz Palacios, a mulatto woman, who arrived with Pánfilo de Narváez’s fleet. Documents of the period also mention Juana Martín and Juana de Mansilla, wife of Alonso Valiente13, “the one who looked after the wounded”.

The latter is mentioned in the Crónica de la Nueva España11 and in Fray Juan de Torquemada’s Monarquìa Indiana.14 The wife of the crossbowman Sebastián Rodríguez, who “was found in the Conquest and served to cure the sick there”, appears in the Indice de Conquistadores y Pobladores de la Nueva España,15 and in a statement by her second husband Cristóbal Hidalgo.

After the Conquest

Indigenous Physicians

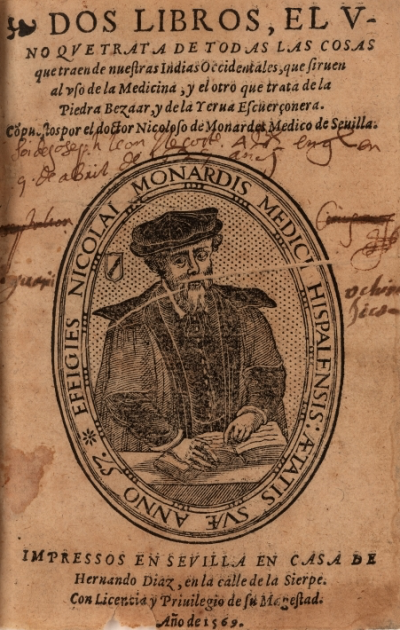

In the first half of the 16th century, the figure of Martín de la Cruz, born in Tlatelolco and educated at the Franciscan College of the Holy Cross, stands out. He was the author of the famous herbarium or recipe book Libellus de medicinalibus indorum herbis, which Juan Badiano, a native of Xochimilco, translated from Nahuatl into Latin. De la Cruz does not appear in the list of titled and untitled indigenous physicians transmitted to us by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún in the Matritense and Florentine codices, but he is among the examiners of other indigenous physicians such as Antón Martín and Gavriel Mariano.16 His workbook was taken to Spain in 1552 by Francisco de Mendoza, son of Viceroy Don Antonio. It seems that the young man was associated with the Sevillian physician Nicolás Monardes (his real surname, of Genoese origin, was Monardi) for the importation to the peninsula of Novo-Hispanic medicinal herbs and, in particular, of the so-called China root – a variety of sarsaparilla – and of the guaiac wood, used for the treatment of syphilis. Such plants were the subject of two publications by Monardes, who was aware of Francisco de Mendoza’s attempts to acclimatise Asian plants in America and of his success in acclimatising ginger.

In later times, Francisco de la Cruz, Miguel García, Joseph Hernández, Antonio Martínez, Juan Pérez, Pedro Pérez and Baltasar Xuárez, all natives of Tenochtitlán, revised and corrected the part concerning diseases and medicines in the Matritense codex between 1567 and 1569. 14 In addition, Miguel Damián, Felipe Hernández, Miguel Motolinía, Pedro de Requena, Pedro de Santiago, Francisco Simón and Gapar Matías, all natives of Tlatelolco, collaborated in the chapters dedicated to “medicinal things” in the Florentine codex. Such chapters were included in Sahagún’s Historia General de las cosas de Nueva España. In the opinion of Somolinos d’Ardois,14 the above-mentioned characters practised medicine in a period after 1575.

Portrait of Nicolas Bautista Monardes (1508?-1588). Taken from the edition of his works by Fernando Díaz Sevilla, 1569.

Indigenous medicines

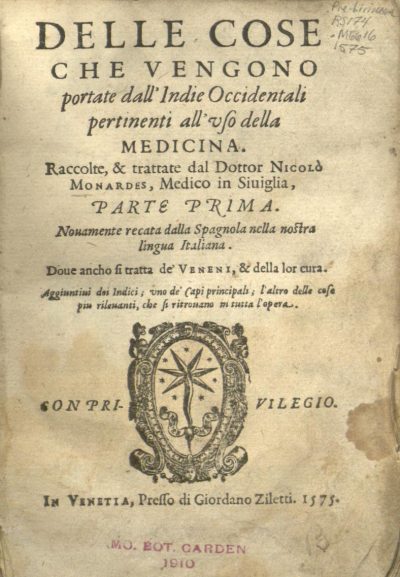

The continued use of local medicinal plants is suggested by the statement made in 1548 by fray Lucas de Almodovar O.F.M., who stated that Bishop Fray Juan de Zumárraga provided the infirmary of the large convent of San Francisco with all that was necessary and “even Castile sent for medicines, because some were not found in this land”.17 In Cortés’ second letter-relation, dated 30 October 1520,18 neither the medicinal herbs nor the medicaments already prepared by the herbalists in the main market of Temixtitán are described. These herbs would later be described – and some also drawn – by Nicolás Monardes19. In addition to the plants used in the treatment of syphilis, the latter imported to Spain and studied the balsams of Peru and Tolu (Miroxilon peruiferumL. and Miroxilon toluiferumL., respectively). He also imported purgative medicines – in particular the root from Michoacán or Jalapa – and made a very accurate description of the tobacco plant (Nicotiana tabacum L.).20 Translations and printings of Monardes’ works soon followed in several European countries. E.g. in Italy they started with the pamphlet Modo et ordine come se ha di usare la Radice Michoacana (Milan, 1570), with the Trattato della neve e del bere fresco... (Florence. Impr. Bartolomeo Sermartelli, 1574) and the pamphlet Delle cose che vengono portate dall’Indie Occidentali pertinenti all’uso della Medicina (Venice. G. Ziletti, 1575)21.

Spanish Physicians and Surgeons

The first Spanish doctor to arrive in America was Dr Diego Álvarez Chanca, physician to Queen Juana and Columbus’ companion.22 In the very year of the capture of the Aztec capital, 1521, the Sevillian Cristóbal de Ojeda, a doctor of medicine, arrived in Mexico. During the residency trial against Hernán Cortés (1529), he declared that he had treated the former tlatoani Cuauhtémoc many times after the torment inflicted on him for burns on his feet and hands. In December 1523, the said physician and the licentiate Pedro López (the first) treated Francisco de Garay, recently arrived from Jamaica, during his mortal illness.

On the other hand, Francisco de Soto, a barber surgeon, was appointed by the civil council as the “official surgeon” of the New Spain capital. But a Latin-educated surgeon soon arrived, i.e. one with surgical studies and practice: Master Diego de Pedraza. When Cortés set out for the Hibueras (1524), he took with him “as physician a Licentiate Pedro López, a neighbour of Mexico, and a surgeon, Master Diego de Pedraza”.24 López, on his way by ship to the island of Santo Domingo, was able to escape from a dangerous shipwreck on a plank.25 Pedraza would later accompany Cortés on his entries into the Pánuco and Jalisco regions. Beatriz Muñoz, a Spanish midwife and nurse, also went to the Hibueras and, according to the statement of her son Sebastián, “was of great service in curing those who were wounded by the wood and nails of the ships, which had been broken and lost in a storm”.24 When Cortés returned to Mexico (1526), he sent for a master from Rhodes to cure his right arm, which had been broken by a fall from a horse.25

When the licentiate Luis Ponce de León had just arrived with the task of conducting the trial of Cortés’ residence (1526), “he got a very bad fever and lay down in bed, and was numb for four days without any sense, and all he did during the day and night was sleep; and after that the doctors who cured him, who were called the Licentiate Pedro López and Doctor Cristóbal de Ojeda and another doctor he had brought from Castile, saw this…”.26 This was probably an epidemic of typhoid fever in which some thirty people perished in addition to Ponce de León.

On 11 January 1527, Pedro López was appointed protomedic of New Spain. He attended Doña Juana de Zúñiga, Cortés’ second wife, and wrote an extensive account of the medicines used, one of the oldest and most important medical documents in Mexico. In 1531, Diego de Pedraza was appointed by the town council as “supervisor of physicians, surgeons and salvers and of all other persons who cure and anoint diseases”. In addition to these, doctors Olivares, who arrived in 1524 under licence from King Carlos I, Sebastián de Urieta, who was “singular in science and experience” and Juan de la Fuente, the future holder of the first chair of medicine at the Royal University of Mexico (1578), practised medicine at that time. The latter denounced Dr. Centurio, of German origin, before the court of the Holy Inquisition because he defended certain doctrines of Paracelsus.

In the second half of the century, in order to organise an effective control of the practice of medicine, King Felipe II issued in Madrid the Royal Decree of 11 January 1570 (Law I of Title VI of Book V).27 However, despite all the royal provisions, a multitude of unlicensed persons were engaged in the practice of medicine.

There were several physicians born and trained in Mexico, such as Juan Haro Bravo de Lagunas, nephew of Dr Francisco Bravo. In any case, in the aspects of health organisation, research and teaching, the doctors who came from the Iberian peninsula were outstanding, such as the second Pedro López, who in 1553 obtained the degrees of licentiate and doctor of medicine from the brand new University of Mexico. He had a brilliant university career, was the founder of the new Hospital de San Lázaro for lepers in 1572 and of the first Casa de cuna (natal unit), a special department of the Hospital de la Epifanía (1582), which functioned until 1604. He was a great friend of the venerable Bernardino Álvarez and assisted him with Dr. Juan de la Fuente and others in his mortal illness (1584).

Protomedic Francisco Hernández, a graduate of the University of Alcalá de Henares, was sent by Felipe II on a scientific mission to New Spain. He remained there for seven years (1571 – 1577) carrying out professional activity, anatomo-clinical studies and natural history research. During the cocoliztle epidemic in 1576, he participated in the first necropsies for diagnostic purposes carried out in the Royal Hospital of San José de los Naturales, together with the surgeon Alonso López de Hinojosos and Dr. Juan de la Fuente.28 Moreover, he travelled on muleback almost the entire Mexican territory to discover and describe the plant, animal and mineral remedies that it could offer to the field of therapeutics. His voluminous notes were not published in his time. But an epitome could be published in Rome (1651), under the auspices of the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynxes).29

Title page of the Italian edition of the second part of the treatise Delle cose che vengono portate dall’Indie Occidentali…. Venice, 1575.

Early medical books

In the shipping lists of Spanish books to New Spain, works by Francisco López de Villalobos (1473 – 1549) are recorded, i.e. El sumario de la medicina, a humorous didactic poem in which he described the effects of syphilis. The peninsular physicians who emigrated to the lands of Anáhuac were probably familiar with the writings of the brothers Jerónimo and Gaspar Torrella, printed at the end of the 15th century, which set out the new guidelines for the treatment of this disease, as well as the clinical histories of several patients treated.

Pedro Arias de Benavides, who arrived with the entourage of the judge Alonso de Zurita, was a good surgeon trained in Salamanca and author of the book Secretos de chirurgía.30 It is rich in quotations from authorities, clinical accounts and therapeutic prescriptions. It mentions contemporary physicians: Valpuesta, Torres, Francisco Toro and, on folio 138 v, Vesalius himself, considered by the author as a “famous surgeon and anatomist”. Ruy Díaz de la Isla, one of the most qualified physicians of his time for the study of the origin and therapy of syphilis and author of the Tratado contra el mal serpentino (Treatise against serpentine disease), is also mentioned.31 Benavides, who resided in Mexico from 1554 to 1564, was in charge of a specialised hospital for the treatment of bubas, probably the Hospital del Amor de Dios founded by Bishop Zumárraga. Due to his long experience, he rejected guaiac wood and sarsaparilla as anti-bubo medicines, replacing them with the more effective mercurial ointments.10 In turn, Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, professor of rhetoric at the University of Mexico, owned a copy of the book of surgery by the Italian Juan de Vigo (Giovanni da Vigevano), probably in the Spanish edition of 1548 printed in Toledo. This surgeon recommended haemostasis by ligation of the vessels instead of that obtained by thermocautery.

Up to the 1550s only three physicians have left written documents, which allow us to analyse their knowledge and their personal approaches: the aforementioned Arias de Benavides, Pedro López and Cristóbal Méndez, who was trained in Salamanca. The latter practised his profession in Mexico between 1534 and 1545, as a protomedic and visitor. On his return to Spain, he published a book,32 in which he describes the first necropsy performed in the American continent on a 5-year-old boy with bladder lithiasis. In addition to the classics, the author cites only one contemporary physician: Dr. Mexía.

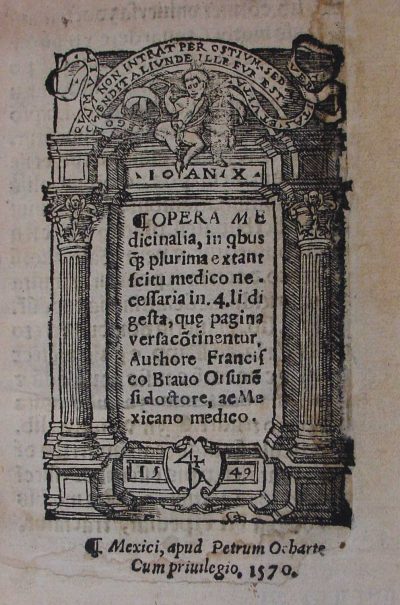

During the second half of the 16th century, the first medical books were printed in New Spain. The printer Pedro Ocharte (Ochart),33 originally from Rouen, son-in-law and heir of the Bressan Juan Pablos (Giovanni Paoli) – the first printer in America34 – published in 1570 Opera Medicinalia by Dr Francisco Bravo35 with a prologue by Francisco Cervantes de Salazar. It is the first medical book printed in America. Apart from a study on tabardillo (heat stroke), we find in it an initial contribution to the examination of the hygienic and sanitary conditions of the population of Mexico, analysed with epidemiological attempts. In the opinion of Somolinos d’Ardois,10 such an attempt recalls the ancient Hippocratic treatise On airs, waters, places. Ocharte also printed the treatise on natural history by Dr. Juan de Cárdenas36 and the second edition of the Tractado breve de medicina (1592), a work of medical popularisation by the Sevillian Agustín Farfán.

In turn, the Turin printer Antonio Ricardo (Riccardi or Ricciardi), who initially worked in Ocharte’s workshop, printed the first books on surgery: Summa y recopilación de cirugía (1578) by Maese Alonso López de Hinojosos,37 surgeon of the Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales, who introduced the use of leeches and wrote the initial observations on dentistry in Mexico, and Tractado breve de anothomía y chirugía… (1579) by Dr. Agustín Farfán. The characters used by Antonio Ricardo were made with elegance and care, particularly the italic or cursive types that resemble those used by Aldo Manuzio and Francesco Grifi.

The scarcity of Novo-Hispanic medical publications is perhaps due to the late institution of chairs of medicine. The first one was instituted in 1578 on a temporary basis – the dean in the New World38 – and was in charge of Dr. de la Fuente. In 1595, the printing house of Pedro Balli brought out the second edition of the book on surgery by Maese Alonso López. That year the Royal University of Mexico obtained the title of Pontifical by virtue of a brief from Pope Clement VIII, granted on 17 October in Frascati. Shortly afterwards, in 1598, a university thesis on medicine appeared,39 the first in America, printed in Balli’s workshop.

What has been said here confirms Germán Somolinos d’Ardois’ accurate assertion:10 “the Spanish or Mexican doctor, who practised his profession at the dawn of New Spain, needed to use for his practice the materials offered by the environment“. In any case, over the course of the century, the experience and knowledge acquired by Europeans were gradually introduced into the Americas. At the same time, the ancestral traditions of the inhabitants of the Americas were passed on and merged with the medical knowledge of the peoples of the Old World.

References

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, pp. 240-376.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p.55.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, pp. 109-110.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p. 571.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p. 240.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p. 244.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p. 338.

- Laín Estralgo P. Historial de la Medicina. Barcelona. Ed. Salvat, 1978, p. 369.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, pp. 376-377.

- Somolinos d’Ardois G. Capítulos de historia médica mexicana II. México, 1979, pp. 148-149.

- Cevantes de Salazar F. Crónica de la Nueva España. 2 vols. Madrid Ed. Atlas, 1971.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p 371.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, pp. 492 y 199.

- Somolinos d’Ardois G. Capítulos de historia médica mexicana III. México, s.a.

- de Icaza F. Conquistadores y pobladores de la Nueva España. Es. Páginas escogidas. México. UNAM (BEU), 1994, pp. 132-133.

- Viesca Treviño C. Y Martín de la Cruz, autor del códice de la Cruz-Badiano, era un médico tlatelolca de carne y hueso. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 1995;25: 479-498.

- García Icazbalceta J. Don fray Juan de Zumárraga. México. Ed. Porrúa, S.A., 1947, 4 Vols. Vol. III, pp 322-325.

- Cortés H. Cartas de relación. Segunda carta. México. Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1993, p.63.

- Guerra F. Nicolás Bautista Monardes. México. Compañía Fundidora de Fierro y Acero de Monterrey, S.A., 1961, pp. 56-63.

- Guerra F. Nicolás Bautista Monardes. México. Compañía Fundidora de Fierro y Acero de Monterrey, S.A., 1961, pp. 64-67.

- Monardes N. Delle cose che vengono portate dall’Indie Occidetali pertinenti all’uso della Medicina. Venecia. Giordano Ziletti, 1575.

- Tió A. Dr. Diego Álvarez Chanca. Puerto Rico. Inst. Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1996.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p404.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p.459.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p.548.

- Díaz del Castillo B. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. México, Ed. Porrúa S.A., 1994, p.510.

- Muriel J. Hospitales de la Nueva España. México. Instituto de Historia, No. 35, 1956, p. 287.

- Fernández del Castillo F. La cirugía mexicana en los siglos XVI y XVII. México. Lab. E R Squibb, 1936.

- Hernández F. Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus. Roma. Vital Mascardi, 1651.

- Arias de Benavides P. Secretos de Chirugía… Valladolid. Francisco Fernández, 1567.

- Díaz de la Isla R. Tratado contra el mal serpentino. Sevilla. Domingo de Ronbertis, 1539.

- Méndez C. Libro del ejercicio corporal y de sus provechos. Sevilla. Gregorio de la Torre, 1553.

- Stols A A M. Pedro Ocharte, el tercer impresor mexicano. Méxicano. Impr. Nuevo Mundo, 1962, p.10.

- Dávila Padilla A. Historia de la fundación y discurso de la provincia de Santiago de México de la Orden de Predicadores… Madrid. Pedro Madrigal, 1596, p. 670.

- Bravo F. Opera Medicinalia. México. Pedro Ocharte, 1570.

- de Cárdenas J. Primera parte de los problemas y secretos maravillosos de las Indias. México. Pedro Ocharte, 1591.

- López de Hinojosos A. Suma y recopilación de Chirugía. México. Antonio Ricardo, 1578.

- de la Plaza y Jaen C B. Crónica de la Real y Pontificia Universidad de México. (N. Rangel, Ed.). México. Impr. Universitaria, 1931.

- Rangel F. Dolores oculorum meripotio. México. Pedro Balli, 1598.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021