Source:El Debate

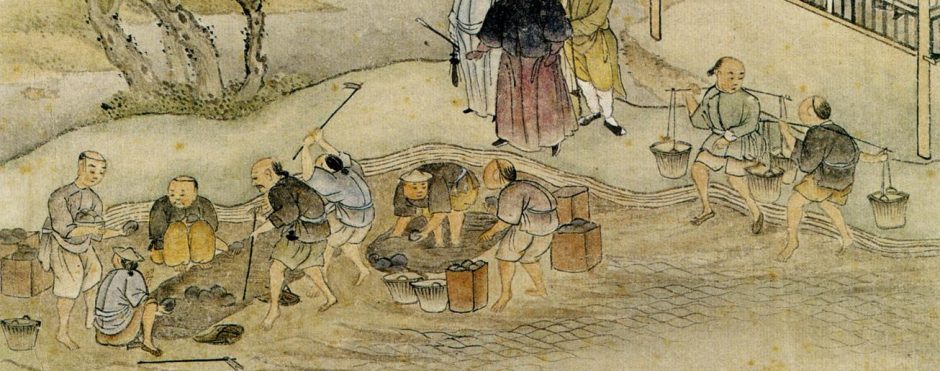

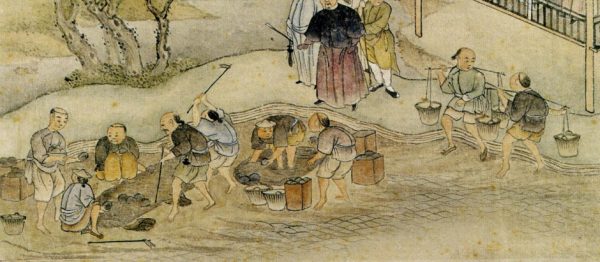

The introduction of opium into China grew exponentially and rapidly reduced the trade deficit. Predictably, what the British saw as an economic solution for the Chinese became a serious social crisis.

The Chinese, children of a civilisation more than two thousand years old, have a high concept of their homeland. In their worldview, the Kingdom of China is the centre of the world, around it, to a lesser degree, are the more or less sinified countries such as Korea, Japan, Vietnam… and, finally, there are the absolutely barbaric regions among which is our Europe.

This mentality was well illustrated when Lord Macartney presented himself in 1793 as ambassador to King George III of England. He came to the Emperor asking for a trade treaty, more ports open to British merchants and a permanent diplomatic presence at Court. English pride, however, met with the Emperor’s indifference. The ambassador who refused to follow the traditional protocol for speaking to the Emperor, i.e. prostrate from the floor, went on to display all manner of English gifts, technology and inventions. The Emperor patronised him, but was uninterested. After offering him a sumptuous banquet, within days he sent him back to London with a letter saying that he had “never appreciated ingenious articles” and that he had “not the slightest need of manufactures from England”.

The issue was not a trivial one for the British. The Chinese self-absorption was causing them a major economic problem: an imbalance in the balance of payments. The Chinese were exporting large quantities of tea, silks and porcelain for which they were being paid in silver, but with no interest in English goods, there was no way of getting the silver back into British hands. Once it entered the Chinese market it never left. When American silver was no longer readily available and Britain began to pay with its own rapidly dwindling reserves, the issue became critical.

Opium: the solution and the crisis

The East India Company, however, soon found a solution. Long based in neighbouring India, they realised they had the solution at their fingertips: opium. The easy production of this addictive drug in large quantities and its smuggling into China was the way to recoup the silver lost through the legal export of Chinese goods. The introduction of opium into China grew exponentially and quickly reduced the trade deficit. Predictably, what the British saw as an economic solution for the Chinese became a serious social crisis. China banned the legal importation of opium in 1800, and in 1813 its use altogether. By 1820, however, probably a million Chinese were addicted to the drug. The problem was also particularly notorious among the ruling classes, officials, even princes. In 1830 the Emperor cried out in an edict:

Opium is flooding the interior of the heavenly empire. The multitude of consumers is growing day by day, and more and more people are selling it; they are like fire and smoke, destroying our resources and harming our subjects. Each day is worse than the last.

The Emperor himself went so far as to consider legalising the drug in order to control it, but in the debate, however, the option of implementing a policy of war on opium ended up being imposed.

Lin Zexu versus Lord Palmerston

Lin Zexu, an exemplary official of high Confucian morals, was appointed imperial commissioner in Canton, the gateway to opium, to try to stamp out the plague. First invoking moral arguments, he went so far as to write Queen Victoria a naïve yet threatening letter that ended thus:

Our Celestial Dynasty rules and oversees a myriad of states and surely has endless spiritual dignity. Thus, the emperor cannot order the execution of anyone without first having tried to reform him by education. (…) The barbarian merchants of your country, if they want to trade for a prolonged period, are required to obey our statutes with respect or permanently cut off the flow of opium (…) You can sift the wicked among your people before they come to China to guarantee the peace of your nation, show henceforth the sincerity of your policy, and lead both countries to enjoy the blessing of peace together.

The letter was not even acknowledged. The British were not prepared to give up such a lucrative business. When Lin saw that words were useless, he imposed effective measures: blockade of ships, expulsion of merchants, confiscation of goods. The new policy caused concern among private merchants who saw their businesses in danger, so much so that the British government even sent a punitive fleet.

Britain’s naval superiority soon put China on the back foot, and China signed a peace agreement allowing British settlement in Hong Kong and agreeing to compensate the merchants for their losses (1840). But Lord Palmerston was not satisfied, and the UK sent a new fleet which even threatened Nanjing, the former capital of the Kingdom (1841). China had to capitulate again.

The Treaty of Nianjing (1842)

The war ended with a highly unequal treaty in which five ports (including Shanghai) were opened to foreign traders and Hong Kong was handed over to the British in perpetuity. Opium continued to wreak havoc on the morale of the Chinese, who now added a great humiliation to their weakness. It would not be the last; over the next hundred years the great Empire would suffer one moral defeat after another, undermining its centuries-old self-esteem. These included a second Opium War (56-60), where British greed was joined by French brutality, which was mainly responsible for the sacking and burning of the Emperors’ elegant Summer Palace in Beijing. The event would remain a symbol of European barbarism in the memory of the Chinese.

Share this article

On This Day

- 1572 Andrés Díaz Venero de Leyva founded the town of Guaduas (Colombia).

- 1578 Brunei becomes a vassal state of Spain.

- 1672 Spanish comic actor Cosme Pérez ("Juan Rana") dies.

- 1693 Painter Claudio Coello dies.

- 1702 The Marquis de la Ensenada was born.

- 1741 Spanish troops break the siege of castle San Felipe in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia).

- 1844 The Royal Order of Access to Historical Archives was promulgated.

- 1898 President Mckinley signed the Joint Resolution, an ultimatum to Spain, which would lead to the Spanish–American War.

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021