Source:ABC

Despite his staunch antislavery stance, Alexander von Humboldt had to surrender to the evidence of the statistics collected on his trip to the old continent regarding the number of Africans subjected to the Spanish Crown and the treatment received by the indigenous people, “infinitely more favorable »Than that of other powers.

By virtue of a very general bias in Europe, there is a belief that very few indigenous copper-tinged natives have survived in America. In New Spain, the number of indigenous people rises to two million, counting only those who do not have a mixture of European blood. Even more consoling, far from extinction, the Indian population has increased considerably over the past fifty years, as the poll and tribute records show.”

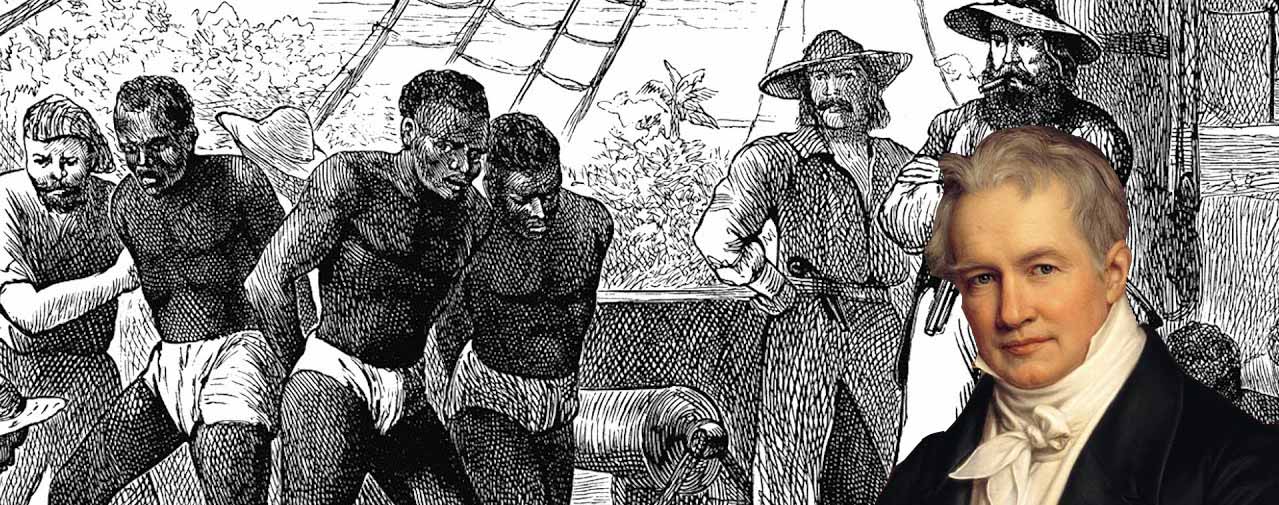

Whoever wrote these words was not exactly suspected of giving the ears to the European colonial empires when it comes to the treatment they gave to the natives after the discovery of America. Moreover, his constant militancy against slavery, between the end of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, made him a great number of enemies in the Spanish Crown, the court of Berlin, and the government of Napoleon Bonaparte. But Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) made it clear during his long research trip through the current territories of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Cuba, Mexico, and the United States, between 1799 and 1804, where he concluded that if Europe had seen with different eyes the richness that existed in the cultural diversity of the old continent, “it would have found solutions to war, oppression and the abomination of slaver”, science historian Laura Dassow Walls assured the BBC a year ago.

What no one doubts today is that that expedition transformed our vision of nature, to the point that some fundamental ideas of current environmentalism still feed on the work of the famous German naturalist and geographer. The proof of his legacy is that 250 years after his birth, his name is the one that more places, geographical features, plants, and animals in the world have in his honor. But what interests us here are his surprising (and more unknown) studies on slavery in America, which two hundred years ago knocked down the black legend spread against Spain about the treatment it gave to slaves and the number of them it had in its domains.

Against slavery

As Humboldt warns in his “Political Essay on the Island of Cuba” (1826), he only wanted to “explain this phenomenon and specify its concepts through statistical comparisons and glances”. And so, with all the data collected during his five years in America, he wrote the most important liberal sermon against this phenomenon in the Atlantic world during the 19th century. So bad was it that John S. Thrasher deleted the aforementioned chapter in his 1856 translation, as it violated one of the pillars of the European economy, prompting the author to protest vigorously in public.

The origin of his research is in the revolution in Haiti, after the slaves of the plantations of the Acul region, north of Saint-Domingue, rose up in 1791. That revolt that culminated on January 1st, 1804, with the proclamation of the first black republic in history, just as Humboldt returned to Europe from his long stay in America, gave him much to think about. The impact was so strong that, in 1807, the trade of Africans with their colonies was suppressed in Britain. In Spain, it was tried four years later. According to Marieta Cantos, Fernando Durán and Alberto Romero in “The pen war: society, consumption, and daily life” (UCA, 2006), the deputy José Guridi Alcocer asked in the Cortes of Cádiz for “a plan to abolish slavery, the regulation that the children of slaves be free from birth or, where appropriate, pay them a salary so that they could buy their freedom in the long run”, but it was met with strong criticism from Cuban deputies and the problem was not resolved.

When the former slaves, now soldiers and officers of an independent army, proclaimed Haiti’s independence in 1804, Humboldt still had not written a word in his diaries about this important event. “Despite this, when he went to Venezuela in 1799 he was already an enemy of slavery. And while he wrote nothing about slaves, he did take a long excursion to the plantations of his well-known slave oligarchs and listened to elite debates about the technological improvement of slavery. In addition, in Havana, he met the Adam Smith of plantation economies of America, Francisco de Arango y Parreño, who had carried out a previous comparative study. The German, however, needed more time and began to write about rebellions, conspiracies, slaves, and slavery until his second stay in Cuba in 1804″, comments Michael Zeuske in his article “Alexander von Humboldt and the comparison of slavery in the Americas” (University of Cologne, 2005).

“The greatest of evils”

This is where Humboldt’s simmering surprises come in light of his stats. “If Cuba is compared with Jamaica, the result seems to be in favor of Spanish legislation and the customs of the Cuban inhabitants. These comparisons show, on the latter island, a state of affairs infinitely more favorable to the physical preservation of the blacks and to their granting of freedom”, Humboldt points out in his “Political Essay on the Island of Cuba”, published twenty years after his trip to America, when slavery was not only still not eradicated, but was flourishing throughout the Caribbean. “It continues to be the greatest of all the evils that have plagued humanity”, he says.

One of the most important results of Humboldt’s work is his comprehensive and detailed analysis of the indian and black population in Spanish-American colonial society. With regard to the first group, according to the director of the Center for Hispanic American Research at the University of Paris X, Charles Minguet, in his article “La América de Humboldt”, our protagonist “managed to sweep away a lot of errors accumulated over centuries by writers of the Black Legend, who had shed torrents of tears on the Indians, without ever having seen a single representative of them.”

80% of the total population of Latin America is made up of Indians, mestizos and mulattos

“The data that Humboldt gives are statistical”, he adds, “and thanks to them, Europe, educated and deafened throughout the eighteenth century by the screams of horror of tearful indianistas, learns that there are, in the Spanish possessions of America, 7.5 million Indians and 5.5 million mestizos. In other words, a total of 13 million Indians and mestizos or mulattos, representing 80% of the total population of Hispanic America. These figures mean that, at the end of the 18th century, the Amerindian population had reached or exceeded the figure assumed on the eve of the Conquest.”

Blacks, slaves and mulattoes

With respect to the presence of the black population in Spanish America, Humboldt also offers, in the words of Minguet, “very detailed, serious and complete data” which cause surprises to the defenders of the Black Legend. From these statistics, the professor at the University of Paris X deduces the following points:

- Between 1800 and 1820, of the 6,443,000 blacks (slaves and free) in all of America, Spanish America has only 776,000. The number of slaves represents only 4% of the total population of Latin America and not 8% as they have claimed. That is to say, between 500 and 550 thousad slaves in a population of 15 million inhabitants, more or less, while in the French and English Antilles, the proportion was 80 to 90% and in the United States 16%.

- The slaves transported to Spanish America represent only the fifteenth part of the total number transported during three centuries by the European countries.

- In the Spanish colonies, manumised slaves were much more numerous than elsewhere: 18% in Cuba, 3% in North America, 10% in the English Antilles. The fact is due to the custom that Spanish owners of giving freedom to their slaves in their last will.

- In Cuba, the free population, among whites, blacks, and mulattoes, represented 64% of the island’s population in 1820.

- And if we examine the Spanish slave legislation, especially the Carolino Code of 1789, we notice that it is far removed from the atrocious catalog of torments, torture, and mutilations provided for in the codes of France and England of the same time. Without a doubt, we know that, often, all the legal provisions dictated in the metropolis were not applied in the colonies. “But let us recognize with Humboldt that the moderation of texts, customs, and the influence of religion allowed a more humane treatment. And that all these elements contradict the European prejudices that attributed abuses and crimes committed by others to Spaniards”, concludes Minguet.

“Slavery was not a Spanish institution”

Our protagonist, given his anti-slavery position, had no reason to whitewash Spain’s policy regarding slavery in its American territories, especially at a time when most European societies were concerned about whether the situation in Haiti could have consequences on their colonies and on “their” slave trade. And in fact, he did not, because he made enemies in Spain many enemies for his uncompromising position against this phenomenon, despite the many arguments he heard from the slave owners.

Some critics have wanted to see in his analysis of Spain in America that the crown financed part of Humboldt’s trip to America, but the truth is that his anti-slavery position in all territories — including the Spanish — grew during his expedition. And yet, “for him slavery was not a Spanish institution, but an institution of the local elites, that is, of the Creoles (criollos). He witnessed it anywhere, also in places where this is not expected, such as in Mexico City”, adds Zeuske.

The Prussian traveler would discover that the Spanish slave legislation was far from the torture and atrocities provided for in the French and English legislation. For Humboldt, the main causes of the most humane treatment received in the territories of Spain were found both in the legislative texts and in the influence of religion and social customs. And he comes to recognize that reality contradicted European prejudices, which attributed abuses and crimes committed by others to Spaniards.

As Juan Sánchez Galera defends in “Let’s tell lies” (Edaf, 2012), and despite the anti-Spanish propaganda followers, the Hispanic monarchs did not consolidate the conquest of America with a clean sword, but thanks to an army of teachers and priests. Faced with those who present the discoverers and conquerors of the New World as cruel genocides, the historian affirms that the Laws of the Indies that ruled life in those colonies were the origin of what we know today as Human Rights. “The Indians, apart from being dispossessed, are full owners of the lands they work, and from the yield of these they pay a tribute or service to their encomendero, who in turn has the obligation to protect and Christianize them. Like any human institution, the encomienda gave rise to certain abuses, and in rare cases, it even degenerated into a kind of disguised slavery“, he defends.

Share this article

On This Day

No Events

History of Spain

26 August 2020

27 January 2021

Communism: Now and Then

23 December 2022

28 July 2021